Laboratory Procedures

Basic dendrochronology procedures of the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory

Dendrochronology is a relatively young and dynamic branch of science based on the extensive record of the past environment and climate that is evident in the biological growth of trees. These records include evidence for both cataclysmic events and patterns of climate change over time, both at local and regional levels. Well-known as the most precise dating method, dendrochronology enables us to study different aspects of the past with annual, and sometimes seasonal, precision over time. Of the numerous definitions describing the essence of dendrochronology, here at the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory, we adhere to Eckstein's definition: "dendrochronology is a science of extracting chronological and non-chronological information from dated tree-rings."(1) The key to dendrochronology and related sciences is tree-ring growth.

Tree-rings are easy to observe in the cross-section of most sawn tree trunks. Each ring is one of the many concentric bands surrounding the pith and all are more or less distinguishable from each other. They are the result of cell formation outwards from the pith (the oldest part of the tree). One ring is produced each year (except in some tropical, subtropical, or other difficult areas), within the growing season. Tree-rings are wider or narrower, brighter or darker and they reflect conditions under which the tree grew, mainly the climate conditions. The ring widths, the anatomical characteristics of the wood, and other features of their growth vary from year to year with changing environmental conditions. In this way, the history of trees and their environment is reflected in their wood structure.

Modern forest trees have tree-rings representing the last few hundred years: exceptionally old trees can be found that have lived for more than a thousand years (sequoia, bristlecone pine, and New Zealand kauri trees are good examples). Wood is preserved that was used in works of art, cultural artifacts, or for construction of buildings, offering a potential record of hundreds to thousands of years. Subfossil trunks that are buried in peat bogs or river sediments have been preserved for many millennia and can take us even farther into the past. Petrified wood exists that grew millions of years ago and was mineralized, but the rings are still evident. This unique biological archive is the subject of study for dendrochronologists.

Samples are collected by coring live trees, extant structural beams, boards, and rafters, and by taking cross-sections whenever possible. For art historical objects and artifacts, the tree rings are measured directly on the object or from a digital photograph, both methods nearly non-destructive. We have an extensive collection of samples from the Aegean and Mediterranean for the last nine millennia, and a growing collection from northeastern North America, including samples from the Late Glacial chronozone. In 2007, we are adding to our Cretan and Cypriot collections, and extending our collection into the northern Balkan area.

Our initial analysis is based solely on the wood and its growth ring patterns. We examine all biological aspects to obtain a comprehensive view of the information stored in the wood structure. After the wood has been studied, we then look to other information about the site, social status of trees (competition for sun, water, and other nutrients), the forest ecology of that region, etc., to aid in the data set analysis, and context of historical samples to complete interpretation of tree-ring analyses.

Laboratory preparation includes sanding and polishing dry samples, preparing wet samples with a razor blade, and microsanding charcoal. The samples are then studied under a microscope using a traveling stage to measure the tree rings at 0.01mm or even at 0.001mm precision. The ring widths are measured for tree-ring dating, and wood anatomical features are noted. We are developing methods for recording additional parameters, such as earlywood and latewood widths and densities, and maximum and minimum densities. Facets such as vessel area and tracheid size are measured with image analysis.

Cross-dating is used with raw measurements or detrended data sets to establish the sequences' placement in time. The principle of cross-dating is straightforward: trees of the same species growing in the same time in the same geographical region have similar tree-ring patterns. Cross-dating allows us to place sequences in time by matching the patterns securely, mainly with a visual inspection, using statistical tests to suggest possible relationships.

Dendrochronology is independent of the other historic and proxy records due to its basis on wood analysis. We are examining the structure of organic material created within a geographic region in the terrestrial ecosystem over time, a feature that is independent of most other records. Interpreting the record of the tree-rings is the major focus of our lab.

The context of the sample - whether from archaeological sites, a historic building, or a work of art - gives us a range of possible dates for the individual rings and the patterns contained in the rings. Dendrochronology in general includes establishing calendar dates for samples and chronologies that include forest trees and historic sequences that securely crossdate; and establishing absolute dates for floating chronologies by securely crossdating the unknown sequences with other chronologies that are absolutely dated, or, if necessary, by radiocarbon wiggle-matching samples contained in the chronology.

With the extensive data sets already collected, we can also determine more about human wood-history. The use of dendrochronology to determine the source of timber, termed "dendroprovenancing", was introduced to solve the questions of imported timber in western part of Europe and subsequently for timber from excavated ships(2). The basic requirement for dendroprovenancing is a dense network of chronologies. A high similarity of the tested tree-ring sequence against the master chronology representing a defined geographic region indicates its likely origin. In this way the Baltic region has been found as the provenance of painting panels used by Netherlandish masters, e.g., Rembrandt, Rubens, and others. The possibilities are literally endless.

In cooperation with other plant, geology, physics, and chemistry research scientists at Cornell University, there are numerous possibilities to extend our field of activities. Volcanic and late glacial research are two potential avenues. Traces of major volcanic eruptions are recorded in tree rings, and their impact can last for years after the eruption. Isotopic analysis of the tree-rings can help us learn more about the chemical signals of these eruptions, and how long the effects remain in the environment. Volcanic eruptions, global warming, El Niño, and other global-scale climatic and ecological events are vital issues, and tree-rings hold records of the past that may help us to understand, and even change our future.

But the key to the Lab and its progress is you! We need samples, please. We would like to work on any and all wood, especially archaeological wood and charcoal, from the circum-Mediterranean and Near East region; and also wood and subfossil wood from NE North America; paintings by European masters (on oak panels especially), etc. Please contact us to discuss. Details on how to collect and package samples are also on the sampling page. Thank you very much for your interest and support.

|

|

Download a more detailed PDF summary of methods and procedures at the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory. |

References

(1) ECKSTEIN, D., 1998: Principles of dendrochronology. In: PARK, W.-K., KIM, J.-S. (ed.):

(2) BONDE, N., TYERS, I., WAZNY, T., 1997: Where does the timber come from? Dendrochronological evidence of timber trade in Northern Europe from 14th to 17th century. In: SINCLAIR, A., SLATER, E., GOWLETT, J. (eds.): Archaeological Science 1995, Oxford: Oxbow Books, 201-204.

Measuring a sample of Gordion wood.

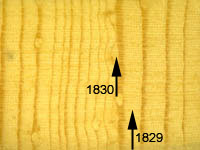

Partial AD 1830 ring and low growth in following years, Cyprus.

Pinus nigra in the Troodos Mountains, Cyprus.

Chionistra, Cyprus, 2007.

Cedar Valley, Cyprus.